Leone's suitcase

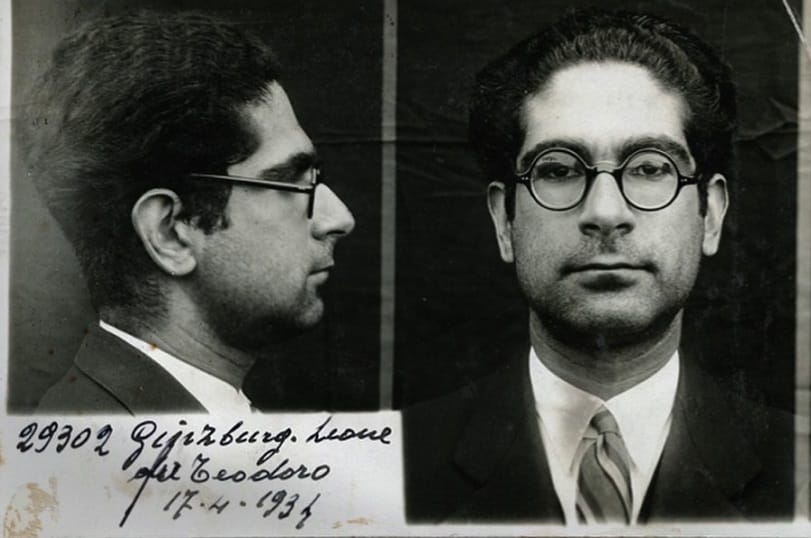

On 13th June, 1940, Leone Ginzburg—writer, editor, translator, anti-fascist—arrived in the remote village of Pizzoli in the mountains of the Abruzzi, and took up residence.

That day he wrote to his aunt, Maria Segré, that the place was beautiful and welcoming, that he had settled in quite well, and that he hoped she would be meeting these difficult moments—of the break-up of the family, of exile, fascism, incipient war—con saldo animo, with a resolute spirit.

Given that he was almost certainly sitting alone when he wrote these words, we can assume that he was also reminding himself to meet his own current difficulties con saldo animo. Ginzburg was Jewish, and had a history of anti-fascist activity, and was therefore now under the peculiarly totalitarian sentence of confino, or internal exile.

He was thirty-four. He would have to stay in Pizzoli until after the collapse of the fascist regime on 25th July, 1943. Which, it turned out, was more or less the rest of his life. In August 1943 he moved to Rome, where, within months, he was arrested at the printworks of an anti-fascist paper of which he was editor; he was handed over the the Germans, tortured, and died of his injuries before they could execute him, on 5th February, 1944.

...

But here he is in Pizzoli, writing to his aunt.

Mi ci sono sistemato assai bene, he writes. I have settled in here quite well. The Italian for some subsets of meanings of the word settle (settle in, settle down) is sistemarsi. It is a reflexive verb. You systematise yourself.

As, occasionally, in English. You might for example settle yourself down in a corner of a room with a book. Reflexively. A little loop of energy, thrown out and cast back, interiorised. There you sit, a knot of flows and circuits, an eddy in the surging currents of the world, a minor settlement. To settle is be caught in reflexivity, the Italian seems to say.

Sistemare, the non-reflexive version of the verb, it might be worth noticing, means something like tidy up, put in order. Settle the affairs of your bits and pieces. But as in English, where you can offer to sort someone out, as indeed you might offer to settle the matter of a spilled pint outside in the car park, sistemare has a range of idiomatic means concealing, but offering, violence. ti sistemo io! for example, would mean, I'll soon sort you out.

...

That first address Ginzburg writes from in Pizzoli, Corso Sallustio 155, is a small terrace, a house of small rooms. He would likely have occupied one only. He was alone at this point, so did not require much space. What would he have done first? He would have unpacked his suitcase. A suitcase of belongings is the antonym of a systematised life, a compacted set of inaccessible items bearing only relations of proximity, not function, one to the other. He would have hung his few shirts in the wardrobe, set his handful of books on a shelf, arranged his writing materials—pencils, a knife to sharpen them, pen and ink, a small sheaf of paper, one or two current manuscripts—on the only table; he would have peered into the corners and cupboards, tried the springs on the bed, opened the window and looked up and down the narrow street, learning the space, taking possession of it; chatting perhaps with his landlord about practicalities.

Here he is then, settled in. Does he have a little stove, can he make himself a coffee? Let us give him a stove. Here he is, sitting at his little table, his window open—it is June, a warm season in the Abruzzi—a little coffee cup between his fingers, wrenched from the thousand delicate contexts and networks of his home town, Turin, his wife Natalia and two infant children, his work at the Einaudi Press (he has several years since been banned from teaching, as a result of the racial legislation of 1938). Bereft then, but con saldo animo, settled in, in only the most superficial sense of the term. He has unpacked his suitcase and made himself a coffee.

...

And so he settles to work.

Editing work. He cannot do any original writing in his preferred genre of dense essay on European writers, history, philosophy, since he does not have libraries and materials to hand. And money is short. Piecemeal editing pays not much, but pays (relatively) quickly. Thus his correspondence for the next three years is dominated by letters to colleagues at Einaudi demanding manuscripts, original texts of translated works, listing errors, explaining delays, hurrying payment, chivying and berating colleagues.

Ginzburg is a cast-iron, unforgiving, hair-tearing editor. In his isolation, he gives himself over to a plethoric mania for correction. For combing text for details. He frustration boils over on the page with wearying regularity.

Everything is wrong with everything he reads. It is all so clear to him, so vague to everyone else. He rails at the mis-transcription of names (“I found three ways of saying ‘Faubourg Saint-Germain”; “the translator seems ignorant of the fact that Trier, Köln and Mainz are habitually rendered in Italian as Treviri, Colonia, and Magonza”; why does he find both Mikjukòv and Miljukow in the same text?); in spite of his exhortation that the copy editors should comb texts, including notes, con pedantesca esattezza, to see that corrections have been entered with the requisite punctiliousness, he finds again and again commas gone astray, diacriticals in various languages not accurately transcribed, lines poorly spaced; he admits that requirements such as that they should change M.lle to Mlle are so many quisquilie, nitpicks, but also cannot stop himself from knowing that not attending to them “casts a shadow of disorder over the edition”.

...

From time to time he gets a reaction.

To read his complaints, by turns furious, petulant, resigned, ironic, he might be a lunatic scrawling tiny writing on the walls of his cell; but they do reply, sounding nonplussed, with reasonably grounds – they hadn’t received his telegram when they responded; they had acted on the telegram the moment they received it; the typescript is on the way.

And sometimes they lose patience too. Einaudi remarks drily that Ginzburg’s changes to the drafts of War and Peace are excessive, and they are surprised at this because these are changes to texts which he himself had prepared. Ginzburg comes out fighting. He is, he says, “vividly pained” by the charge; he reminds them that he did not have the original text in front of him when he corrected the first volume; that their surprise is therefore out of place; they when they threaten to print without sending him drafts to oversee, they are only threatening themselves since, he says, people do not buy Einaudi because they love the ostrich (the logo of the press), but because the texts are accurate and legible; if books go out half-right and half-wrong, when respect for the reader is diminished, they will abandon the press; he concludes that he will continue to try to work miracles of speed, but the day has only twenty-four hours, and their letter took three days to reach him.

With somewhat withering self-deprecation, he apologises for yet another delay in supplying a manuscript but adds that “la mia rapidità di lavoro ha un limite invalicabile, quello dell’esattezza” - “the speed at which I work has an insuperable limit, that of precision”.

Ginzburg’s world is going to piece in an unstoppable slide of inaccuracy, of capricious transliteration, of misplaced parentheses. And there is little he can do. He is sequestered like a medieval theologian locked in a monastery in the forests of the mountains of an ill-travelled region, a theologian for whom the cosmos is a copied manuscript, copied and recopied, into which the foul fiend guilefully enters by way of a misplaced umlaut, a wrong accent. Writing God’s love into the world only makes for an an error-strewn code of creation, going always awry, throwing up illogicality, bug, heresy; and only twenty-four hours in the day to combat it, and Ginzburg’s glasses are broken, and he has to go to the dentist; has to help Natalia (when, after a few months, she arrives) with the housework; he has the flu or his family has the flu; the world is falling apart one n-dash at a time, faster than he can put it right; he will go to his grave in just a few dwindling months, months in which he will break his glasses again, get the flu, again, witness the arrival of another child (Alessandra); he will go to his grave with nothing resolved, a flurry of uncorrected manuscripts and typescripts, books printed on poor paper where the ink rubs off on your hands, books with missing pages, with error, always error; the whole of the Western canon at the mercy of time, entropy, ignorance and neglect; a work of tired and lazy monks barely keeping the cosmos rolling, a cosmos glitching, blinking, about to go out forever; for want of a semi-colon.

...

It is in the nature of the job, of course. I have had diligent editors, in the past, get exercised about the number of semi-colons I use; I have known American proof-readers with an award-winning line in tetchy, weary sark; my mother-in-law, opening my new book for the first time, found a typo within thirty seconds and read it out slowly for my edification.

And so while I have, God knows, lost patience with typographical error in books, I feel a little exposed to the glare of Leone; I would wilt under his ruler. I am mildly dyslexic and astigmatic, my spelling has been described as approximate, the shape and detail of words blur and deform the harder I look at them; to carry a memory of a spelling from a book to a page is a labour for me, I have to look from book to screen again and again and the seconds drip through my fingers; I have struggled for years with languages – the endlessly small but telling variations of Ancient Greek won’t stick in my head, and I have only the vaguest idea of where accents go on Italian, French, Spanish, or their proper direction; all this tinctured by the worry that all knowledge stems from a grasp of fine detail, detail which I do not merely fail to grasp, but in my chosen métier, literally to see; I regard it as a genetic failing, my father and my brother having that grip which I and my mother lack and lacked; and while I know that neurodivergence is only a healthy natural variation of the collective mind; that to hunt down and fix this one lingering error would represent an increasingly mad mismatch of effort and outcome; that, in short, I am what I am; well that’s all very well, but I know that in Leone’s judgement I would be on the right hand side, tumbling down under the scorn of his milk-bottle glasses; that Giulio Einaudi, if I had worked for him in those years, would have had to walk through wearily to my little office, yet another steaming withering invective from Leone in his hand, and I would have had to account for no end of faults, errors, oversight, sin.

And not only that, but with a final irony I have found, in transcribing Ginzburg’s laments and fury for this post, that I had miscopied the page reference of at least one piece of his correspondence, had mislaid the accent on rapidità, and had even mistyped the word corrrect (which I can only hope was a small act of unconscious rebellion on my part).

...

Leone Ginzburg’s wife, Natalia, received permission to join him a few months after he arrived in 1940, with their two infant sons, Carlo and Andrea. They arrived on 13th October. They moved into a larger place, although it was still not very large, and the family spent the rest of his confino together.

On the first anniversary of his arrival in Pizzoli, Leone Ginzburg had written to an old friend that Natalia per fortuna sta li. Natalia fortunately is there. He would have been editing, or corresponding furiously with his fellow editors; she was writing fiction, her first novella, La strada che va in città, The Road Which Leads to the City.

Later, after Leone's death, when Natalia was trying to make some money to support herself and her children by writing and—inevitably—editing for the Einaudi press, she wrote a short essay, entitled Inverno in Abruzzo, in which she recounted some details of their hard life. She writes that Leone, for all his troubles and evident reluctance, became a fixture in the village; they insisted on calling him dottore, and would come to him with all manner of problems. He dealt as best he could with them, with conspicuous politeness and patience. And, she wrote, for all that their life was one of hardship and confinement, those moments when they worked together on either side of the little table in their one room – he editing, she writing her first novel – while the the children were asleep, were the happiest they lived together.

Member discussion